"lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

"lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

08/09/2017 at 15:49 • Filed to: America, Car industry, Chevrolet, Cadillac, Ford, Chrysler, Culture, Youth, Bill Mitchell, Harley Earl, 1960s, Counterculture

2

2

2

2

"lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

"lorem ipsum" (nothing123456789)

08/09/2017 at 15:49 • Filed to: America, Car industry, Chevrolet, Cadillac, Ford, Chrysler, Culture, Youth, Bill Mitchell, Harley Earl, 1960s, Counterculture |  2 2

|  2 2 |

Disclaimer: This is an excerpt from my dissertation. I love cars so much I spent a year researching and writing 11,000 words, despite professors telling me it wouldn’t be considered a “legitimate”¯ academic subject. Then, I bought a 1952 Chevrolet pickup as my daily driver.

Conclusion:

Even as late as

1959, many industry insiders thought that the trend of be-chromed and be-winged

automobiles would continue into the future, evolving in an ever-more

exaggerated fashion- after all, inferring from sales data, it would certainly

seem as though that style was popular.

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

There were indications of an approaching

change, though: a switch in design leadership within two of the Big Three, a

rapidly increasing share of the market taken up by foreign imports, a changing

youth culture (influenced by European tastes and the emerging counter-culture) dictating

a larger segment of the auto-buying demographic, and a public fed-up with

paying too much for a form-over-function product. Smaller external factors helped contribute to

the styling shift and downsize as well, such as domestic manufacturers, looking

to reclaim lost European markets, adapting their cars for a more global taste.

1961 Lincoln Continental, photo courtesy of Ford Motor Co.

The role car designers played in the styling shift is a little complicated. For both Chrysler and GM, looking at their model lineups before and after Virgil Exner and Harley Earl left each respective company shows a clear separation in style. And, interviews and biographies indicated that their replacements, respectively Elwood Engel and Bill Mitchell, favored sharper edges and simpler designs than their forebears. It is also important to note that the roles of Mitchell and Engel in the styling shift at their companies were not singular; this styling shift did not spring from the minds of trend-setting car designers alone. Ford’s styling team remained the same throughout the styling shift, and this points to something larger: Engel was one of the most important designers on their team, and he replaced Exner at Chrysler after Ford had already released their fresh, crisp 1960 models. So, Engel helped bring Chrysler the style of the 1960s, and Bill Mitchell helped GM with the same, but for Ford, the impetus to revise their design standards came from elsewhere.

In no small part

were automakers pressured into this style change by the general consuming

public. Throughout the second half of

the 1950s, European imports bit into an increasingly larger share of the US market. These cars were smaller, better-engineered,

and more simply styled than their American counterparts- the impression this

gave to consumers was that these foreign companies were spending money on the

actual functionality of the product rather than its appearance; an honest

business practice. Compounding the

problem of the popularity of European cars was the declining reputation of

domestic manufacturers. The Big Three

were being lambasted by buyers for selling poorly-assembled machines which grew

more expensive each successive year for no apparent reason: one of few tangible “benefits”¯ to the increasing cost were design revisions that often

reduced

functionality.

Not only was Europe delivering a superior automobile to the American masses, they were also emerging as global taste-makers in music, art, and culture. Britain, especially, was a leader in this department, and American youth were particularly receptive to the trends coming from across the Atlantic. In each place, somewhat simultaneously, a consumer protection movement gained traction, designed to discourage corporations from pursuing the types of dishonest practices favored by the Big Three. Some of the philosophy behind this movement- the focus on integrity, authenticity, and honesty- would meld into a burgeoning counter culture with a youthful epicenter. Many high-profile figures from both the USA and Europe, including musicians who were enormously influential among baby boomer, were proponents of this counterculture, and used their autos to make statements surrounding it, shining a spotlight on the car.

The baby boomer

generation was reaching driving age around the year 1960- and their parents- unprecedented prosperity afforded them a considerable amount of disposable

income. Both of these factors, coupled

with the sheer size of the youth population, pressured automakers to cater to

the baby boomer demographic. Further,

because products with the perceived quality of youthfulness were so fashionable,

the tastes of the youth fast-became the tastes of the public. The Big Three had no choice but to adapt to

the changing conditions, and began producing cars that appeared more similar to

the honestly-styled, practicality-minded European models. After all, that type of machine appealed more

to youth than the chrome-encrusted status-symbols of yesterday.

Finally, the period immediately following World War II was one of extreme excess for the US auto industry. Manufacturers rabidly increased the size, power, price, and bright work on their cars without necessarily making them perform any better or more reliably. While the newly-built US interstate system could cope with the land yachts emerging from Detroit, the medieval streets of Europe were simply too narrow for many to seriously consider purchasing an American product. This lead to a declining share of the market abroad for the Big Three- these once-had, now-potential sales provided even more incentive for them to produce smaller and more sensible machines. And, gradually, subsequent to the release of the compact trio in 1960, the ground lost was being reclaimed.

This

styling shift is an odd one. The vast

majority of every car produced and sold in the United States exhibited similar

styling- rounded, bulbous shapes adorned with chrome, tailfins, bubbly

windshields, and gaping grilles- and, besides a few murmurs in 1959, everything

seemed to be going business-as-usual. But over the next few years (ending for the most part in 1964), the

entire US car industry, still in tandem, headed in the opposite direction. Round, amorphous shapes were muscled into

cleanly-sculpted surfaces with definition, creases, and sharp edges. Chrome was stripped away, grilles shrunk, and

once-distinct elements became cohesive as the manufacturers strived to design a

product with perceived integrity and honesty. The influences governing this shift were myriad, but they resulted in

the car, once more, reflecting the values and mood of American society.

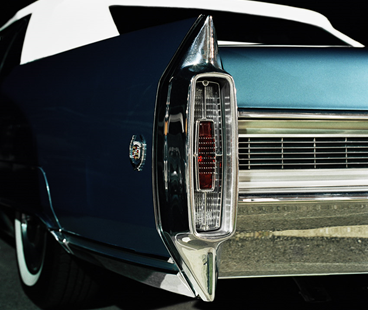

1965 Cadillac tailfin, photo courtesy of Simon Ladefoged.

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! Roger Huntington, Where Did the Inches Come From? , (Popular Mechanics, 111:1), p. 172

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> lorem ipsum

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> lorem ipsum

08/09/2017 at 16:01 |

|

I imagine there’s something to be said for the “keel” design element in automotive design, enough for a whole other dissertation. How did Elwood Engel manage to make that one successor to tailfin design so dominant in American luxury design that it drove “slab-sided” design tendencies all the way into the eighties?

The Powershift in Steve's '12 Ford Focus killed it's TCM (under warranty!)

> lorem ipsum

The Powershift in Steve's '12 Ford Focus killed it's TCM (under warranty!)

> lorem ipsum

08/09/2017 at 16:44 |

|

Excellent overall. My only comment is that your conclusion notes the consumer protection trend, but it’s not discussed in the body of your paper. I know that you’re focusing primarily on design trends, but noting it when also discussing the larger cultural and economic trends that affected automotive design would be appropriate. In addition, it’s an argument that supports your central thesis, and tacking it into the conclusion seems like an afterthought.